How to Misuse Story Structure for Video Game Narrative Design

The more time I spend working in the games industry doing what I do in the realm of Narrative Design. The more reactions and raw emotions I see towards the idea of Story Structure Guides. On a good day the reaction towards them is one of keen interest and understanding. On a bad day it is a look of disgust, horror and pure hatred.

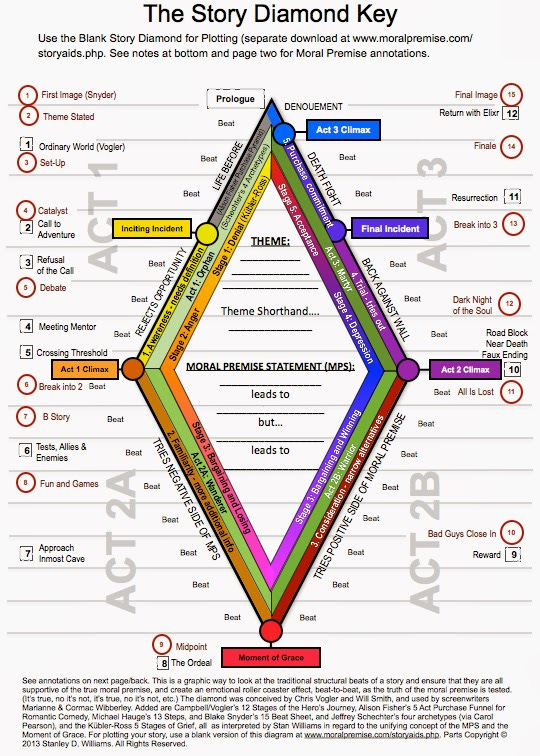

These various story diagrams, cheat sheets, books and outline templates are everywhere. They are mainly geared around screenwriting but are often useful for other forms of writing and story plotting. Some are nothing more than 3 statements to guide your thoughts. Others are....well....this thing...

I'm not here to convince you that they're an essential tool for all narrative designers. Each creative has their own process, I'm just going to share mine. However I will say that there different kinds of storyteller and you should respect their approach to problem solving. The sooner you start treating others' creative processes with the same respect you would like your own to be treated the more you will learn from them and they you.

So to begin, here are the two basic types of storyteller:

Pantsers - Those who get an idea, sit down and write the crap out of it. Editing, fixing and rewriting on the go or afterward.

Plotters - Those who plan out their story in as much detail as possible before sitting down to write. Preempting roadblocks with a loose roadmap to steer their writing.

The reality is that most of us do a mix of raw unfiltered writing and hyper detailed planning. Some lean heavily on one side over the other but there will come a point where the plotter just needs to stop messing with diagrams and actually do some damn writing. Meanwhile the pantser will hit a major roadblock and will need to break down the problem before being able to continue.

The modern myth of the writer is that they are all tortured pantser artists. (An interesting mental image) A myth that often extends to narrative design. You know the one, the muse speaks to the the writer and the words just flow out of their fingertips. Getting the muse to speak to them is the problem because the muse can be cruel. Drink, drugs, and a montage later. Somehow the story has been finished, but at what cost?

It is a myth that personally stopped me of doing any kind of professional storytelling for most of my life because I don't do words gud most of the time due to my dyslexia. I need time and a plan. Also diagrams are cool! That is why all this stuff is so useful and fascinating for me. It's how I tap into my creative energy.

Some will find this useful and will hopefully nod along as they read. Some will make that dismissive "pffft" sound, give up halfway through reading and then write a subtweet about this post. They know better than me, at least when it comes to their own creative process so go them!

Misuse for working in a Dev Team

Game development in most cases is a major collaborative effort. It unites business, creative and scientific minds under the shared vision of making a piece of entertainment for other people to enjoy. It is a process of many different things happening in parallel and at different stages of development. Organised chaos is the best and most favourable way to describe it.

If you are part of the narrative group on a project you need to be able to work within the chaos and do whatever you can to champion the story of the game to the wider team. Just as the level designer knows their part of the process is the most important, the network coder theirs, the UX artist theirs, etc. etc. You know deep down that narrative is the most important part of the game, the glue that holds it all together. The thing that will be delivered into the minds of players via the act of playing the game. So if everyone else believes their part of the process is the most important one. You need to be able to show them the game's narrative in as short an amount of time as possible and with as much detail as you can without melting their mind. They need it for programming the combat systems afterall, so don't break it!

This is where story structure diagrams are at their most useful.

It is far better to get everyone on the team intimately familiar with the key elements of a game's narrative as you collaboratively make it. Than it is to have it all sat unfiltered and unread on a wiki page or in a series of google docs. Far better to have everyone understand what the narrative is doing as it ties the game together as it grows over time. As it changes from tech demos to vertical slices, to alphas, to betas and to release.

A 30 minute meeting of you explaining the story in front of a diagram of the key beats will stick in people's minds more than the hefty tome that is the story bible. The bible is still required but only for those who need it or want to read it for fun. (Sidenote: The for fun readers are often the best feedback givers) Also if you can talk through the story with as little friction as possible you will get more feedback on it. If that feedback comes with a note asking to see more, you know you have got them hooked. Then you can unfurl the red carpet and take them deep into storyland.

Plot out your story along your structure diagram of choice and then show it to people. As they stare at it, give them the high level synopsis. Your beginning, middle and end. Even if they have heard it a thousand times before give them the basics. Then step through the diagram explaining each beat in the amount of detail your current audience requires. Using the structure of the diagram to highlight the narrative intent of a given moment.

It doesn't matter if you've got a complete story or just the rough idea of one. The sooner you break it down into its key parts, the sooner you can get the rest of the team as excited about it as you are. Better still is if you can use it to start building a shared story language within the dev team. You want environment artists talking about how their work informs the narrative journey. How their magic makes your magic better and vice versa. If you're all using the same terminology the easier those conversations become.

Misuse for Growth

If like me you find these story structure theories fascinating and you see stories in terms of beats, sequences, acts and movements. Embrace them regardless of what other storytellers you like and admire say. The moment I realised the idea that they are a bad writer's crutch was a really bad take, one often made in a very gatekeeper-y way that should be ignored. Was the moment I started becoming a better narrative designer. They became a way for me to talk to and build stories within the patterns I have always seen them fall into. They work for me.

Basically find or make the structure that speaks to you and your narrative sensibilities the best. If you are an ardent hater of such things I'd argue you've not found the one that fits your style yet. I challenge you to do some open minded digging. This is because even if you don't use them to organise your own work you can use them to learn from others. They are a great tool for growth as a storyteller.

Take a story structure you know inside out and apply it to the entertainment you consume. You will learn so much from doing it. Just make it your interpretation of both the thing you are analysing and the structure you are using. Break down a story your way, then google to see how others have broken it down and compare the results. You will quickly learn what key moments in a story always stand out to you and which ones you miss. Then use that as a springboard to learn more stuff. If the break down raises questions in your mind. Use that as a springboard to learn more stuff. If the break down does not fit the piece of entertainment you applied it to. Use that as a springboard to learn more stuff.

You get the idea!

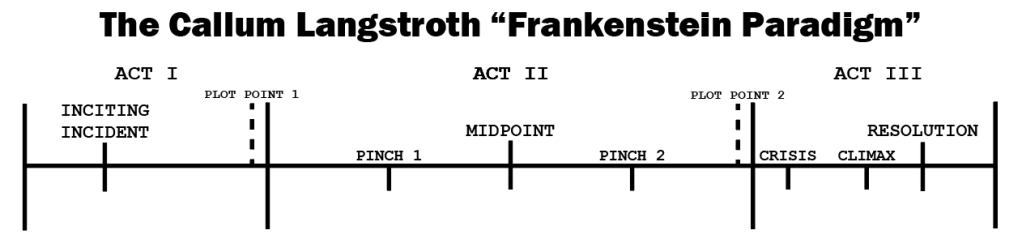

The Frankenstein Paradigm

Some of you will stick with the story structure your forebears taught you. By forebears I mean George Lucas and by George Lucas I mean Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey. Others will obsess over saving cats from trees. A few will champion that five acts is the best number of acts to have. While others will insist all narratives are one act of continuous story. A few will say there is no such thing as structure then go on to explain their game's story in terms of beginning, middle and end. Personally I use everything. I find some structures are better lenses for certain stories. With each on having its own priorities and flavour. My general rule of thumb is to have one main structure you present the story with. Then if elements of other structures help you emphasise the things you really want people to know. Use them.

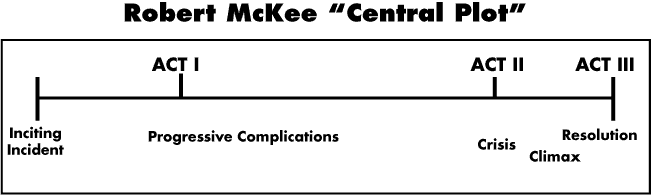

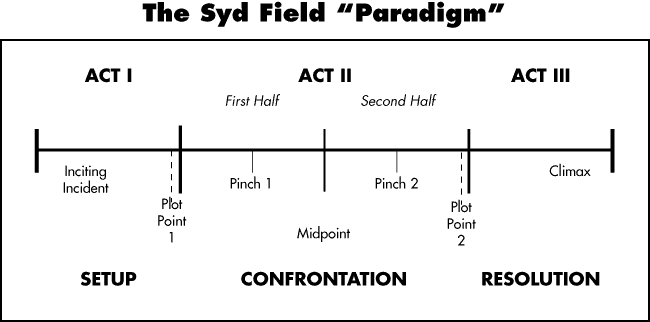

My personal go to just because I find it is versatile is a mashing together of the work of Syd Field and Robert McKee. McKee's story structure is great for emphasising thematic growth from beginning to middle to end. While Field's paradigm gives you a way to describe the action that builds up to McKee's key beats. This approach also gets bonus points because Robert McKee despises video games. So adapting his story theory to my own ends is the best way to prove him wrong. (I'm not spiteful I promise!)

Here they are in their most well known forms because like Pokemon there are multiple variants and evolutions of these structures.

The Frankenstein Paradigm as I call it, takes Field's paradigm and puts more weight into the Inciting Incident and adding in the Crisis, Climax and Resolution elements of McKee's structure to tie it together. Giving you more detail across the whole story rather than just the middle.

Here's a quick and dirty breakdown:

Act 1 - Setup

INCITING INCIDENT - The thing that kicks off the story. The problem that needs fixing, often something that ruins or alters the protagonist's life or worldview.

Plot Point 1 - The choice or action that causes the protagonist to start fixing the problem the INCITING INCIDENT gave them.

Act 2 - Confrontation

Pinch 1 - The overarching challenge and tests the protagonist faces in their pursuit to fix the problem.

MIDPOINT - The problem pushes back against the protagonist. The true issue behind the problem and INCITING INCIDENT is revealed.

Pinch 2 - Stuff gets a lot harder, like really hard. The challenge and tests push the protagonist to the limit.

Plot Point 2 - The choice or action that causes the protagonist to face the true conflict at the heart of the issue behind the problem.

Act 3 - Resolution

CRISIS - It all boils down to this. The moment that defines your story and the protagonist's journey. The Ultimate Challenge of the INCITING INCIDENT at its most potent with the only way of overcoming it being the protagonist making a fundamental change for better or worse.

CLIMAX - That moment of extreme relief or dread when the protagonist overcomes or is consumed by the ultimate challenge of the CRISIS. The immediate entertaining results of them making that fundamental change.

Resolution - The longer term effects of that change and how the world of the protagonist has been changed by the journey from INCITING INCIDENT to CLIMAX

Is it all nonsense? Yes.

Does it make sense to me? Yes.

Can I use it to explain and tell a story to others? Yes.

I will add and remove elements from the paradigm depending on how the development of the story goes. This is because sometimes that high level view of a story doesn't need to have everything in it. Some times is just needs to say:

Act 1 - Setup

Mario and Peach are having a great time, Bowser kidnaps Peach, Mario vows to save her.

Act 2 - Confrontation

Mario does a bunch of crazy stuff and reminds the player what it means to have fun as they experiment with the power ups and mechanics of the game. Eventually Mario reaches Bowser's Castle.

Act 3 - Resolution

Mario faces Bowser in his final, most dangerous form and ultimately defeats him, it is epic. Mario and Peach go back to having a great time.

I've just found that in most cases the Frankenstein Paradigm covers the key beats in enough detail that it paints the picture of the story in a person's mind when you run through it with them.

Like any structure it can be applied to the game's story as a whole, an individual level, a sequence of events, a scene, a combat encounter, a multiplayer match, a progression tree. Basically anything and everything narrative touches in a game. Just use the bits that make sense to what you are explaining and try to thematically link it together. Stripping back or adding to the level of detail and intent of a beat as you see fit.

Most importantly challenge the assumptions of the structures you use. If rules were meant to be be broken, guides are meant to be ignored. Put your CRISIS in Act 1, your MIDPOINT in Act 3. As long as it makes sense to the story you are telling throw the rulebook out of the window. As long as it tells a compelling narrative via playing the game who cares? Just make sure the rest of the team working on crafting that story can still follow along.

One key thing to remember when applying this structure (or any structure really) to anything game related:

In Film the rule of thumb is often 1/3rd of the script is for Act I and III. 2/3rds is for Act II.

In Games the rule of thumb is often 1/5th for Act I and III. 4/5ths for Act II.

This is because Act II is the meat of your story. Where the action (the playing) will happen. The more time you spend away from that the less playing your players are doing. Unless of course the narrative is the focus of play, as it is in narrative driven games. In that case falling back to the 1/3rd, 2/3rds rule of thumb works best.

Conclusion

Did I plan out this post to prove my point on using structure to guide storytelling?

Nah, I pantsed the heck out of this post. It is what felt right for this piece of writing. Me gathering my thoughts on it all, then fixing it afterwards. Like I said, use and misuse these tools as you see fit. There is no one true way to tackle storytelling.

One thing I will say to end this post with is that you should never solely rely on this stuff to plan out and/or tell a story. Story structure works well because it reduces things down to their bare essence to codify them. That gives it a lot of power. Use it as such to push forward your part of the game making process. However remember that same power when misused quickly leads to generic storytelling. Use it with all the other things a good story and game needs. Use story structure for what it is, one tool among many.

Follow Up Reading

If you want to really dig into the pseudoscience of story structure here is a short recommended reading list to get started.

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee

Screenplay: Foundations Of Screenwriting by Syd Field

Into The Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them by John Yorke

Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction by Jeff VanderMeer

The Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human, and How To Tell Them Better by Will Storr

Note: I've stayed away from game story and narrative design books with this list, that's a post for another time.